I normally find it rather easy to sketch out my feelings about a book. And it’s always the feel of a book that’s most important to me. I don’t especially care about the particulars of the plot or level of tension or all those other things that are supposed to go into making a good book. Hey, I don’t even care if the book is good. If it feels right, I like it. It’s that simple.

I normally find it rather easy to sketch out my feelings about a book. And it’s always the feel of a book that’s most important to me. I don’t especially care about the particulars of the plot or level of tension or all those other things that are supposed to go into making a good book. Hey, I don’t even care if the book is good. If it feels right, I like it. It’s that simple.Figuring out how Light on Snow feels, however, has turned out to be rather complicated. I know what the feeling is, of course. I can hold it in the centre of my chest, and in the space behind my eyes, I can turn it over in the hands of my imagination and say, “That’s rather nice,” but how can I put it into words?

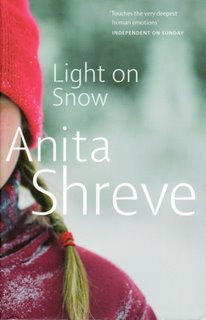

The main problem seems to be my reluctance to try and define the book by just relating the details of the story. In a lot of the books I read, the story gives no indication of the feel. Sometimes the feel is contrary to the story. To describe Kafka’s America, for example, as “the story of a boy who goes to America to find his fortune” is easy and (mostly) accurate. But it doesn’t tell you how acutely the novel made me feel the absurdity and pain of human existence. In Light on Snow, however - a book whose feel I can only sum up with two words: sensitive, understated - the feel of the book flows expertly from the plot itself. The descriptions in the book are prosaic and functional. In many cases my ignorance of this particular cranny in American culture turned objects and actions into broad, half-imagined brush strokes. What poetic language Shreve does attempt feels somewhat clumsy and pretentious.

So, Light on Snow is a sensitive, understated book about a father and daughter who have moved into an isolated country house to escape the memories of a tragedy. One winter day they chance upon a baby that has been left to die in the snow. And that’s the book. The rest of the story flows naturally, does not cover anything especially mind-blowing, but has such a gentle heart that you can’t help but be moved - has a cast of such likable characters that you at once understand their grievances with one another and hope desperately to see them resolved. In the end my only disappointment with this book was the fact that I only have space in my bookcase towards the bottom. After I clear out all my uni stuff, I’ll have to put it in a more deserving space.

Next, on

No comments:

Post a Comment